It's gonna be interesting, folks.

By the end of 2023 we could be as close to normal as we've been in three or four years. Most of you aren't going to like what you see. For maybe 2/3rds of us, it's going to be difficult to find new customers in the future. With rebuy rates under 40%, this means we're going to contract. It's quite possible that, if we managed a $30,000,000 business in 2019 and a $42,000,000 business in 2020 and a $39,000,000 business in 2021 and a $33,000,000 business in 2022 that we'll manage a $28,000,000 business in 2023. Factor in some inflation and you won't like that one bit. But that's where 2/3rds of us are headed.

Those who worked hard on customer acquisition as a growth tactic in 2021/2022 will be light years ahead of those of us who enjoyed all of the profit from the COVID-bump and are now looking at our situation wondering what to do next.

The near-term future is one where it is really, really hard to convince somebody who hasn't purchased from your brand to purchase from your brand. If the customer can get a comparable item on Amazon and have it delivered tomorrow, well, there's no reason for the customer to evaluate your brand. It's been like that since 2010 to some extent. It's worse today.

If you don't have a robust customer acquisition plan, one that goes beyond "spend more money with Facebook and Google", one that doesn't blame Apple (or for my catalog readers, one that doesn't blame the co-ops), you're going to have a fighting chance in 2023. If you are blaming others and saying "well, it's hard to acquire customers, not my fault" ... then it is your fault.

On the merchandise front, many clients are going through a dramatic transition. 2019 is the right comparison when looking at 2022.

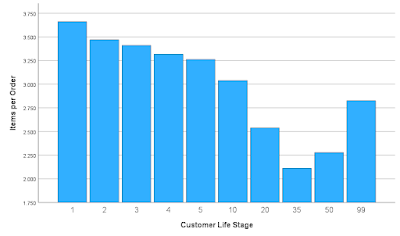

- 2019 = 1,000,000 customers. 1.6 orders per buyer. 2.3 items per order. $40 price per item. Sales = $147.2 million. 3,680,000 items sold.

- 2022 = 800,000 customers. 1.65 orders per buyer. 2.2 items per order. $52 price per item. Sales = $151.0 million. 2,904,000 items sold.