In the comments section, ask a question, or email me your question (kevinh@minethatdata). If I get a reasonable number of credible questions, I will create a blog post series around your questions.

Here are some of the questions I field.

How do I acquire a new customer without spending money or without giving away margin dollars via discounts and promotions?

Why is it so hard to reactivate older customers? Before the economy collapsed, reactivated customers were a gold mine. It's almost like the customer has no memory anymore.

I sell branded merchandise, and you seem to have no answers for improve my business. How can I compete when everybody else is selling what I am selling?

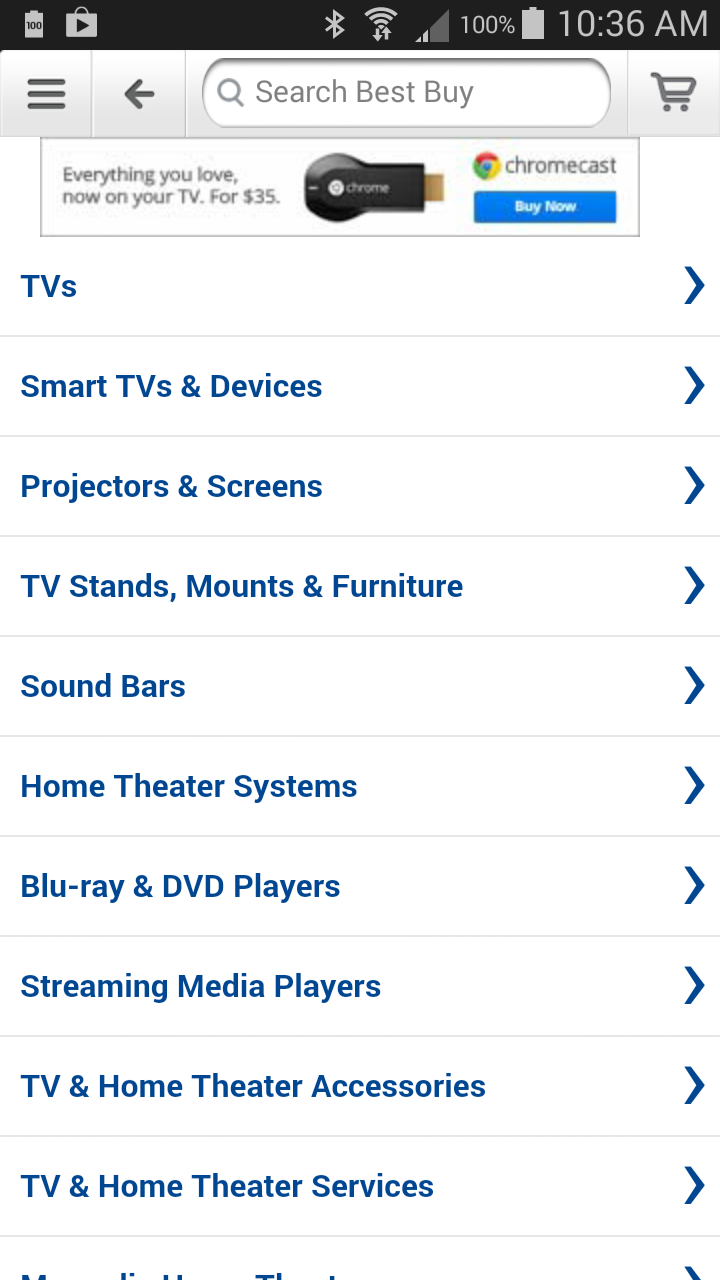

Showrooming is overrated. Your mobile and e-commerce presence actually help stores, though it doesn't seem to manifest itself in sales increases. I guess I don't have a question, I just really enjoy joining the omnichannel discussion.

Why don't Executives ever listen to what I have to say?

Why don't Analysts ever produce actionable findings?

Everybody says I have to be omnichannel, but the customers I acquire from all those other channels have low value and tend to not scale to manageable quantities. Am I doing something wrong?

Can I grow my business by extending existing product categories?

Can I grow my business by cutting styles by 30%?

Can I get my customers to spend more by offering unrelated product categories?

What do I do if the vendors I source my merchandise from are constraining their merchandise assortment? Long-term, won't this hurt my business?

More than half of my file purchases via discounts and promotions. How do I reverse course and get my file purchasing merchandise at full price once again?

Is there any way to pivot my business from a 65 year old customer to a 45 year old customer while still selling the same merchandise assortment and still mailing a lot of catalogs? Can we just employ a best practice for creative that appeals to a 45 year old?

Why aren't customers age 25-34 as loyal as the rest of my customer base?

Why are the three months following a first purchase so darn important?

We raise prices on new merchandise, but find that our customers are then less likely to embrace new merchandise. How do we ever achieve acceptable gross margins when our customers simply won't spend enough money with us?

Don't you think that the environment out there is so promotional that we must also be promotional, or we'll be out of business?

Should we respond to what our competitors are doing, or should we chart our own course?

Our business model is so unique that what you talk about is meaningless to us. How could anybody possibly help a company as unique as ours?

Does it matter if my customer is 70 years old? Sure, my customer was 55 years old in 1999, but now that my customer is retiring, won't every customer who will retire in the future pass through my niche, thereby enabling my business to reap the rewards of a properly managed business model?

Why do I need a younger customer when Baby Boomers have all the money?

Why are more than half the names given to me by the co-ops not buyers from the product category that comprises my business model?

Why are so many conferences employing some version of "pay to play"? Do conferences not earn enough money from those in attendance? Can I trust the message offered by the conference organizers if vendors are paying for speaking slots?

How can I ever come up with enough truly new, unique merchandise when my competitors knock-off what I invent within six weeks, and sell the knock-offs at a lower price?

Isn't it more important to focus on the customer than it is to focus on merchandise? Without a customer, you cannot sell merchandise, correct? Therefore, marketing is more important than ever, and that's where I need to spend my energy. Besides, our merchandise is fantastic, amirite?

Doesn't it make logical sense that if I outsource my marketing activities to smart vendors then my business should improve significantly? Hiring the best talent at the lowest possible price has to be good for business, right?

Why is it that we keep making improvements to our website, we keep improving conversion rates, and yet, sales don't increase? How is that mathematically possible?

Isn't it smarter to be a $100,000,000 business earning $5,000,000 profit per year than a $90,000,000 business earning $9,000,000 profit per year? Who cares about profit when you can earn market share and damage the competition in the process?

How do I get my customer to act the same way in all channels?

Am I going to be required to offer the customer free two day shipping in the future, and if so, what promotional levers will I be able to use, because free shipping promotions really goose sales when business is slow?

Does it make more sense for me to be a vendor to Amazon than to continue as a standalone direct marketer?

Who is an attribution vendor who "gets it"?

Don't you think that if we could nail the attribution issue that we would know where we should spend money, and as a result, we'd be much smarter marketers? Isn't attribution the thing that is holding us back? This is like a puzzle, and we just need somebody to show us how the pieces fit together. Why does the industry struggle with this concept? And could you tell us, for free, how the pieces fit together?

Why do you write so many blog posts? I'd be a lot happier if you spammed me less. And while I am at it, why not offer your loyal readers more free, actionable information?

How could you possibly grow a business without a catalog? It's got to be impossible, don't you think? Name one brand that was able to get past $100,000,000 in annual sales without a catalog?

How could you possibly grow a business using a catalog business model? I mean, sure, customer loyalty would improve, but at what cost? It's too expensive to put paper in the mail, and nobody under the age of 50 even cares, right?

Retail is doomed, don't you think?

What do you think is the next innovation in omnichannel retailing? This has to be the most exciting time ever, in retail. I just love seeing how everybody responds to the omnichannel movement.

How do we ever get a customer to care about email marketing? Unless we offer 20% off or free shipping or some sort of gift, we don't have any engagement. Is email really just a promotional channel for customers who don't want to pay full price for our merchandise?

Why do vendors, trade journalists, conference organizers, and consultants obsess about social media when almost nobody generates any business from social media? Is it possible that the rules that drive business for vendors, trade journalists, and consultants are fundamentally different than the rules that drive my business, or are these people really misguided?

Our whole business model is based on traffic from Facebook and Google. What do we do when Google changes their algorithm and we're unfavorably impacted?

Why is it so hard to find one personalization case study that increased total company net sales by at least 10%?

Isn't it better to mail an individual customer 35 catalogs a year instead of 25 if it means that the customer spends more? Isn't it better to have a big customer file than a profitable customer file?

I have a catalog. I have a website, fully integrated with the catalog. I have an app, for free no less. I fully leverage Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Instagram. I use A/B testing to optimize my website. I use a leading catalog contact frequency vendor. I partner with all the major co-ops. I have up-sell and cross-sell programs. I have triggered email programs. I pay the best search vendor a pretty penny to capture the customer on Google. I pay affiliates for 5% of my orders. I pay a newly formed catalog agency for thought leadership. I make sure that every single visitor to our website sees retargeting ads, even if the visitor is engaging with sites that have nothing to do with commerce. I have YouTube videos, one even managed to go viral. I pay agencies for social media sentiment. My net promoter score is in the top 10% of my industry. I spent a year building a world-class customer database, allowing my staff to answer any question they can imagine. I have a loyalty program for my best customers, I give 20% off plus free shipping for first-time buyers. I'm doing everything right. And my sales are not increasing. Why?