Two metrics ... ROAS and CAC ... are quite popular in digital marketing, and for good reason ... each metric is easy to calculate. Furthermore, each metric essentially measures the same thing.

ROAS = Return on Ad Spend. If you generate $1,000 in sales and you spend $500 to generate the sales, ROAS = $1,000 / $500 = 2.00.

Now let's assume that the AOV is $100. This means you generated $1,000 / $100 = 10 customers.

If all of those customers are new (and they generally aren't new), your CAC or "Customer Acquisition Cost" is $500 / 10 = $50.00.

So now you have a lot of metrics, but you don't have a lot of intelligence. That's a bad combination.

We're one metric away from having something useful.

If you know your "Profit Factor" ... the percentage of sales that flow-through to profit prior to fixed costs, we have something useful. This allows us to convert ROAS and CAC to a more meaningful metric ... "Profit per Order".

- Total Demand/Sales = $1,000.

- Ad Spend = $500.

- ROAS = $2.00.

- CAC = $50.00.

- Profit Factor = 40%.

- AOV = $100.

- Customers = 10.

- PPO (Profit per Order) = ($1,000*0.40 - $500) / 10 = ($20.00).

At this point, you have something meaningful.

You cost your company $20.00 of profit to generate each of 10 orders.

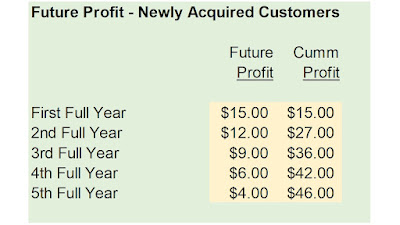

If, after five years, your customers have a CLV of, say $14.00, you made a terrible decision.

If, after five years, your customers have a CLV of $72.00, you made a great decision.

You will not know if you made a terrible decision or a great decision until you convert ROAS / CAC to PPO ... Profit per Order. Once you do that, you compare PPO to CLV and you have actionable information.

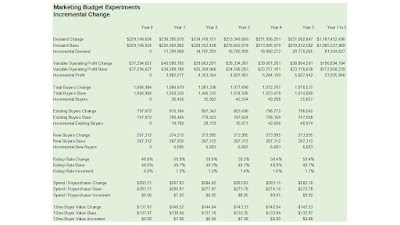

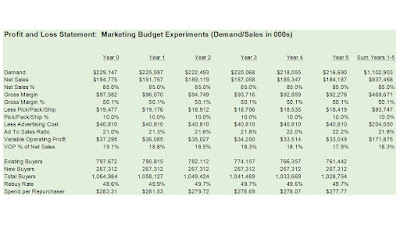

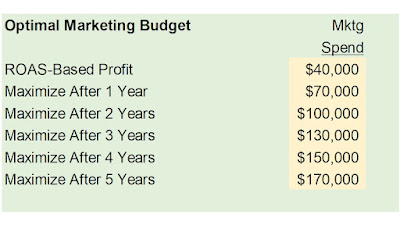

In Hillstrom's Marketing Budget Experiments, the secret to the whole puzzle comes down to two key factors.

- Law of Diminishing Returns in Marketing Spend.

- Ratio of PPO to CLV.

Not a lot of people know how to quantify the Law of Diminishing Returns.

Not a lot of people measure the tradeoffs between PPO and CLV.

Figure those things out and you are well on your way to helping your company achieve a healthy future!

P.S.: As we'll see tomorrow, CAC and PPO are essentially the same metric ... with PPO just being more useful.